|

Where Love Has Goneby Craig Stark 5 February 2026 |

Part IV: Case Study #1

When we first pursue a career, we almost always start out as students. This is especially true of the bookselling trade because the bar of long-term success is high. Frankly, not

many clear it. There's so much to learn, and some of it isn't always easy to grasp. But if you stay with it, make it a point to educate yourself by whatever means, and apply that knowledge

to selling over time, at some point success will almost inevitably happen - if for no other reason that many others will give up early, stubborn focus on selling higher volumes of

low-dollar material, and/or remain largely ignorant of what's durably important to succeed. If you're somebody who doesn't give up, sooner or later you'll likely become not only

a successful bookseller, but also a teacher.

Teachers can take many forms. Some lecture in front of groups at seminars, some create YouTube videos, some simply write how-to content and publish it, etc., and some of us don't even

consider ourselves teachers at all but teach notwithstanding - indirectly, that is, by example. The grand irony of teaching is that it forces you to forever remain a student as well. Ask

any teacher, and they will tell you that teaching is a much faster method of reinforcing (sometimes refining) what you already know because there's a responsibility to get it right when others are listening. It's also a faster method of learning what you don't know but need to - and this often leads to scrambling to catch up to where you need to be. I like to think of this species of learning as a strong deterrent to making an ass out of myself.

One of the things I discovered about bookselling early on is that, if and when you assume the role of a teacher, your effectiveness as a seller becomes significantly more powerful,

especially if you take it upon yourself to teach your potential buyers why they should get up off their wallets and buy your stuff.

A brief example: I had the good fortune years ago to purchase an early 1800's atlas of North America. It wasn't a first edition, but after recalling that it was published shortly after

the Lewis and Clark Expedition, I pondered if it was the first atlas to publish Lewis and Clark's mapping changes that surfaced as an outcome of their exploration. The dates seemed align

plausibly. After what amounted to some minor digging, it turned that it was what I suspected it might be. When I later consigned it to an auction house, the agent I was working with

wasn't overly optimistic about its potential value at first because it wasn't a first edition, but neither was he aware of its being the first published atlas reporting Lewis and Clark's

new mapping. When I told him this, he perked up, then included this in the catalog description, and its hammer price well exceeded what he originally expected it would. Is a working knowledge

of history a potential asset to a bookseller? You tell me.

Of course, pertinent knowledge isn't always held in your head. Sometimes you have to go out looking for it. Research. And this brings me to the first case study in this series, The

Small Loan Racket, a modest but somewhat uncommon little book that pricing history showed some ho-hum outcomes of $10 to $15.

What struck me as intriguing in spite of its apparent low value were a few subtle clues. For example, the topic was finance, but the author was unfamiliar to me, a mild surprise

because at one point in my own bumbling career, I had spent serious time studying finance books and successfully buying and selling many dozens of titles, a majority of them published

in the 20's and 30's, before and after the stock market crash. And this was a Depression-era publication, ca. 1934, squarely in the shank of those hard times, and a flashpoint for

booksellers. Also, the specific topic - loan sharking - triggered another flashpoint response in me: crime. Worse, crime committed on the poor. Anyway, I bought it on one of the

major online venues as a kind of flyer for something in the vicinity of $10. As a plus, it seemed to be in remarkably nice condition, and there was only one other copy available

for sale at the time.

After receiving it, the first thing I discovered was that the stated author was a pseudonym, and better, a pseudonym of a pseudonym. Pseudonyms, of course, have been abundantly

used in the publishing industry for decades, if not centuries. Sometimes they're used to mask something like gender, or an author's departure from a genre where one is well known

to one that's a breakout, or perhaps to protect privacy where disclosure could damage one's present career, suppress litigation from named or thinly disguised persons in a book, etc.

But this author had doubled down on it. The stated author Charles Corzelle was a pseudonym for Charles M. Grant, which was in itself a pseudonym of P. R. Williams, an almost

unknown hack. That raised a red flag for me. Perhaps this was something in the name of name laundering? If so, why?

Notably, AI trotted out the following in a search of The Small Loan Racket on Google: "The book is an expose' on the predatory lending practices that proliferated during the Great

Depression." And later: "The book is cited in legal and historical scholarship as an early primary source for understanding the evolution for predatory lending and the 'democratization

of credit.'" Total bullshit, it turned out to be. Far from being an important expose' of loan sharking, it was in fact written to support the repeal of the Small Loans Law for no

other reason but to enable the Wagner Accounting firm, a known loan sharking entity of Milwaukee that charged usurious rates of interest, to continue to circumvent it and also to

shut down part of its competition - oh, and along the way prevent the Wisconsin legislature from enacting laws that could more readily be reinforced against them.

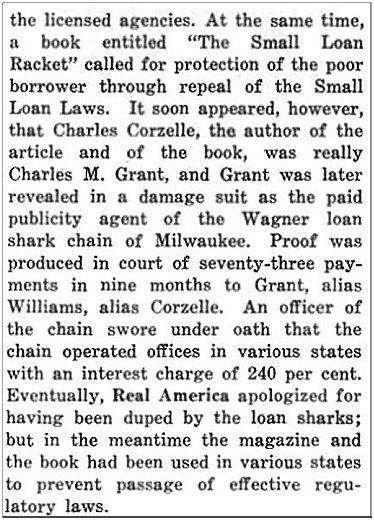

Newspapers from the era were a huge help in digging deeper. Corzelle's book, arguing for the protection of desperate borrowers against loan sharking, was revealed in government

testimony to be nothing more than propaganda which falsely supported a repeal of the Small Loans Law, a law which in turn had allowed suspect lenders to make small loans at considerably

higher interest rates for far too long. Here's a pertinent newspaper clipping:

Eventually, an apology was issued from legislators for being "duped" by the loan sharks. In any case, the takeaway here is that Corzelle's book, far from being a jewel of

"legal and historical scholarship," was fraudulent in intent from the get-go. Most AI content is accompanied by the disclaimer that they might not get it "right" about everything.

In this case they couldn't have been more wrong, and think of the booksellers and their customers who have been duped over the years into thinking otherwise. How does that saying

go? Repeat an untruth often enough and it transmogrifies into "truth." From what I've seen so far, AI gets tripped up here often.

To protect the seller, I'm not going to publish the original listing from which I purchased the book here, only state that it was exceptionally brief, citing only the author,

the page count and this vague evaluation: "good condition." Also, there were several accompanying photos that showed only the outer binding of the book. This is the typical approach

of so many sellers now, snapping a few photos and tossing in a line or two of text, if that. The effect of this approach is to put the burden of research almost solely on the

shoulders of potential buyers. I think we can all agree, however, that most buyers aren't willing to spend more than a few moments looking at a listing - and thus, this particular

listing failed to reach its potential. After I listed it and included the above information in the description, it sold in two days for $100.

So often, it surprises me just how much value can be built into more than just a few books. When I'm shopping, therefore, I look for this potential in books, and yes, occasionally

I still pull the trigger on items that I'm not 100% sure of. Or succeed at reselling for a significant profit. Ultimately, the more you know or the more patience you have researching

what you don't know, the less guessing will figure into this process.

So, this is my first case study. An example. Just one way to build value into a book. There are many other ways to get this done as well, and I'll discuss several more in coming articles.

What I can't do is tell you how to make decisions on what to buy, only say that, minus some hard historical pricing, it requires a kind of listening, and not the kind that's done with

your ears. What I can do is assert that it's possible with many books. And that the reason it's possible - and profitable - is that most of your competition will go away once you take the trouble to make it happen.

Ultimately, your protection against your competition isn't what other sellers have done to acquire inventory worth reselling; it's what they've haven't done on the path to putting

their crap up for sale. That's when the "secret" comes into view. That's when you stop paying attention to the perishable tricks of the trade - things like sales velocity, rankings,

volume, scanners, bloggers who claim they can show you how to make millions, gadgets engineered to spot winners, apps that promise to increase efficiencies, and who knows what

else that comes next. That's when you wake up to see that your ASP (average sales price) matters more than anything. Get this, grock it, and you'll wake up one day and see high-value

inventory come magically into view in the very venues these "paint-by-number" sellers peddle their own wares. I guarantee that you won't find this advice in any Bookselling for

Dummies book. And it doesn't matter if it do. It's already inside you, waiting to be unlocked.

Questions or comments?

Contact the editor, Craig Stark

editor@bookthink.com