|

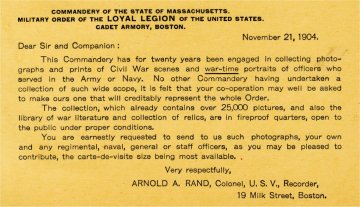

<<< Continued from previous page As early as a decade within the War's end, active efforts were made to collect and preserve artifacts from the battlefield, along with photographs and wartime portraits of Civil War officers. This card, dated November 21, 1904 from the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Massachusetts Commandery - one of the oldest veterans organizations in the country - references a collection that already included 25,000 pictures, a library of war literature and a collection of relics. It contains a solicitation, "You are earnestly requested to send to us such photographs, your own and any regimental, naval, general or staff officers, as you may be pleased to contribute, the carte-de-visite size being most available."

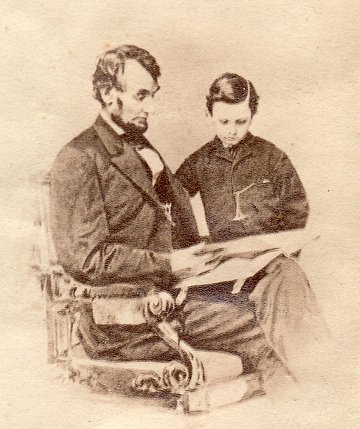

Of course, the extremely rare and premium Civil War images are better suited to the realm of the major auction houses; however, there still remains much opportunity for the average bookseller who runs across paper lots of ephemera at auctions and estate sales to profit from the escalating interest in Civil War photographs. Photography was a relatively new technology at the time of the Civil War, having made its public debut only a few decades earlier in 1839. As the technology evolved, various photo processes overlapped. During the Civil War, several different photo processes were in use: Daguerreotypes, tintypes, stereoviews, ambrotypes and carte-de-visites, which are albumen photos mounted on photographer's card stock. Image collecting is further specialized by topical themes. The presence of any of the following attributes will make a photograph more desirable to a collector: Firearms; swords; uniforms; regiments; subjects identified as being from a particular state; soldiers attached to a particular branch of service; and full length shots. Full length shots are more coveted than bust shots, not only because fewer full length photographic images were produced but because more of a soldier's uniform is visible. Any weapon discernible in a photo will increase the value. Outdoor shots are rarer than indoor portraits and, therefore, more valuable. Casualty rates during the Civil War were very high on both sides of the conflict; approximately 25% of the men who fought in major battles were wounded, captured, lost or killed. Due to this, any period photograph will be markedly increased in value by knowledge of the sitter's identity (ID), preferably annotated on the body of the photo at the time the photo was taken. Be very careful of any photograph that appears to be marked in modern ink. An authentic ID'd Civil War photograph will exhibit ink qualities consistent with its era. The Civil War and the medium of photography fit together like a hand in a glove. New recruits would eagerly line up to have their portraits taken. Also, as troops passed through towns, they would have their photos taken by local photographers to send to their loved ones by mail. As a waning photo process in the 1860s, daguerreotypes are the most uncommon and valuable photographs, comprising less than 1% of all Civil War images produced, and rarely found "in the wild." Most Civil War images encountered at flea markets, antique stores and auctions are carte-de-visites and tintypes. The carte-de-visite was an albumen print measuring 2 ½" by 3 ½" inches mounted to a photographer's card measuring 2 ½" inches by 4". Unlike daguerreotypes and tintypes, albumen photos were produced using negatives, so copies could easily be made. This format lent itself to the mass production of photo images of famous people. Since media was limited to the newspapers, the faces of famous politicians and high-ranking Civil War officers on carte-de-visites were widely collected, much like sports cards of today. The average citizen was eager to see what their heroes and enemies looked like. Photograph albums were specially designed to hold these small photo cards for display in Victorian parlors.

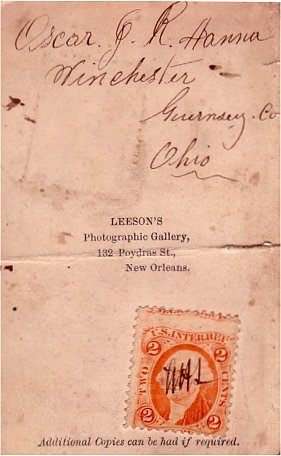

An important identifier to help date Civil War photographs was the tax stamp in use from August 1864 to August 1866. The U.S. Government passed a law that required a tax stamp to be attached to the back of photographs and cancelled by the selling establishment, presumably to raise money for the war coffers. The stamp value was proportionate to the cost of the photo with a 2 cent stamp required for images costing less than 25 cents. Many types and colors of stamps were used, with the blue 2 cent "playing card" stamp specifically used during the summer of 1866. The presence of a tax stamp always conveys a higher value to a photograph because it definitively dates the photo to the Civil War era.

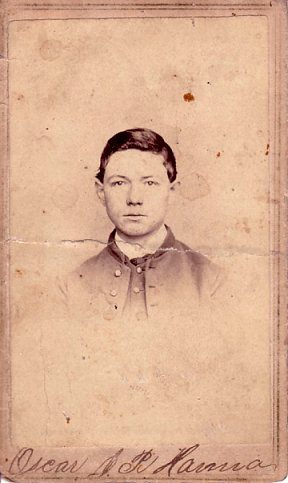

Not only does the tax stamp help in dating a photo, but it can also be a tip-off to a possible Civil War connection. The carte-de-visite photograph of Oscar J.R. Hanna was found at a local estate auction loosely mixed in a bag of old paper. Upon first glance, the Civil War connection was not immediately apparent because the bust shot showed very little of the boy's uniform. As a matter of fact, Civil War uniforms were often varied, particularly in the early years of the War, and are not always recognizable to the untrained eye as being of military origin (especially uniforms worn by Confederate troops).

The tax stamp, however, served to date the photo between August 1864 and August 1866. Upon closer examination, the Civil War uniform was discernible, as well as a hand written signature on the face of the photo. On the back side, the same name is inked, along with the words "Winchester, Guernsey Co., Ohio." The photographer's backstamp identified the location as New Orleans and the studio as Leeson's of 132 Povdras Street. Historical research confirmed that New Orleans was Union-occupied at that point in the War. Whenever a name is present on a photograph, the next logical step is to utilize a search engine to see if any information is readily available. By doing so, I was able to discover that Oscar J.R. Hanna later gained some importance in the political realm, having become a Presidential elector for Michigan in 1896, with his name cited in The Political Graveyard. Additional links that are helpful for researching a name inscribed on a Civil War photograph are: The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System Both links confirmed that Oscar J.R. Hanna enlisted in the Ohio Signal Corps Regiment. Based on that information, I was able to learn the actual date of Oscar Hanna's enlistment from this site: The Signal Corps in the War of the Rebellion The last site also confirmed that Oscar Hanna served with the Signal Corps in the Department of the Gulf, which corroborated the location of the photographer in Union-occupied New Orleans. As you can see, the presence of a name on a photograph allows the sort of in-depth research that makes history come alive and conveys value to a common photo of an ordinary young soldier. Found discarded in an assortment of old papers at a local auction, Oscar J.R. Hanna's creased and stained photo realized an astounding price of $139.00 on eBay.

< to previous article to next article >

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|

|