|

Becoming an Antiquarian Bookseller

Part III: Condition Matters

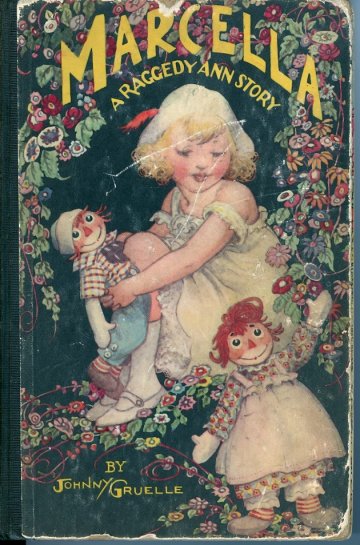

Rookie bookseller that I was, I immediately went home and looked the titles up on BookFinder and AddALL, thinking that looking at what other sellers were asking was the best way to price a book. (Looking at current market prices is part of pricing a book, but for an antiquarian bookseller, it is not the only part. See "Knowledge Adds Value." There were about three copies of Marcella in first edition listed online for about $250-500. I was thrilled, imagining the hefty profit I'd make on this title, for which I paid about $7. However, when I read the descriptions of the sellers, I noticed some differences between their books and mine. Yes, my book was a first edition, but it was missing the illustrated box in which it originally appeared. Also, the other copies were in fine condition. Mine was not. It had a faded spine, roughed up edges, and a scratch down the picture of the face of the girl on the cover. Inside, a few pages were torn at the margins.

My book was worth exponentially less than the other three first editions offered online. Worse, did I really want to list a book in such poor condition in an effort to sell it only to have customers associate my business, Book Hunter's Holiday, with the idea of "good titles, less than stellar condition"? I had a similar sense of dread with the other two titles, which I hadn't bothered to check carefully at the sale. Turns out they were both ex-library copies, which would diminish my asking price to about what I had paid for them in the first place. Hmmm. Apparently, building an antiquarian book business means that one must have the ability to do more than memorize the names and points of issue of collected books. One must also be able to discern the difference between a book in good enough condition to make it saleable and a book whose condition does not justify the effort of selling it. A used bookseller might be happy with the books I mentioned above, but there is a difference between antiquarian booksellers, who usually sell a particular copy of a book - a first edition, a signed copy, an association copy, a copy in a unique binding, a copy in the finest condition - and used booksellers, who usually offer books of all kinds and conditions, largely to people who want reading copies. The book world needs both kinds of sellers, and both kinds of sellers serve a specific purpose. The point is to determine which type of seller you want to be and to work toward that goal. In the case of the antiquarian bookseller, condition matters. A lot. After this failed foray buying books just because I was so excited to find them, I resolved to pay closer attention to condition. While a price-clipped dust jacket, an inscription, or a couple of small closed tears on a dust jacket might be acceptable, faded or darkened spines, pages or boards beginning to separate from the spine, pen or pencil marks in the text of the book itself are not. Soiling and water damage are almost always unacceptable unless so mild as to be unnoticeable. I'm the first to admit that such criteria are subjective and might be altered depending on the rarity of the book, like the time I found a book from 1882 in its original, chipped and torn dust jacket. An 1882 dust jacket is uncommon enough to be desirable in just about any condition, so I bought the book. Additionally, any two booksellers might disagree over the difference between a fine and a very good, but all antiquarian booksellers ought to be able to recognize a copy in good, fair, or poor condition and ought to keep books in these lower grades out of their inventory unless they are so rare that any condition is acceptable. The now defunct, well-known journal for booksellers AB Bookman's Weekly (aka Antiquarian Bookman) had a very usable list of condition grades for sellers. Though the journal is no more, its condition grades are timeless, and provide a good rule of thumb for most antiquarian booksellers. From AB Bookman's Weekly, November 16, 1998: "A thriving antiquarian book trade is largely dependent on the effectiveness of catalogue and mail-order bookselling. Transactions by mail are possible as long as buyer and seller recognize the importance of accuracy in describing the condition of the books offered for sale. Terms used to describe condition of books are as varied and numerous as the creativity and imagination of bookmen can produce. When confusion reigns over descriptions by advertisers or quoters, dissatisfaction is the inevitable result.

>>>>>Click here for page two>>>>

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|

|