|

The Ballad of

|

|

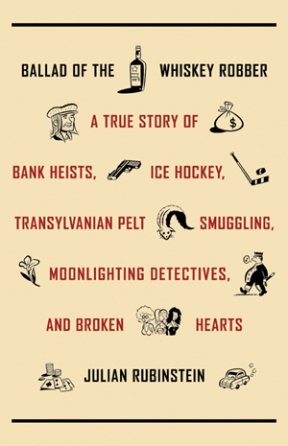

Imagine going to live in a country where you don't speak the language, and most of the words look something like this: Satoraljaujhely. In this very foreign country you are planning to embark upon years of painstaking research on the life and times of an outlaw folk hero in a tumultuous post-communist world - for your first book. Takes guts. Put guts together with great writing ability, a real nose for research, and a sense of the ironic, tragic, and humorous and you have a winner - Julian Rubinstein's Ballad of the Whiskey Robber: A True Story of Bank Heists, Ice Hockey, Transylvanian Pelt Smuggling, Moonlighting Detectives, and Broken Hearts (Little Brown, New York/Boston, 2004).

Satoraljaujhely, by the way, is the maximum security prison on the Hungarian-Slovakian border where Attila Ambrus, aka "The Whiskey Robber," has been held since December 2000. He will be there for at least another five years.

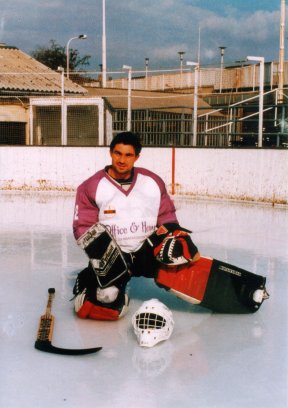

In the meantime, thanks to Julian Rubinstein, his story has generated not only a critically acclaimed book but also a song, "The Ballad of the Whiskey Robber" (music and lyrics by Julian Rubinstein), a popular drink*, and possibly even a movie - Warner Brothers has purchased the rights. When Rubinstein first heard the stories coming out of Hungary about Attila Ambrus, a destitute but dashing rogue who had politely robbed 29 banks and post offices, absconding with nearly a million dollars, he thought it was an interesting tale. When he learned that Ambrus had crossed the border from Transylvania into his homeland of Hungary on the bottom side of a train and had also tried his hand at pelt smuggling, Zamboni driving, goal-tending for the Hungarian URT ice hockey team, some grave digging, a daring prison escape, and a good share of gambling and womanizing on the side, he knew where he was going - and packed his bags. The beauty of the book is this: While the hero of the story captivates us with his wacky disguises, his presentation of flowers to acquiescent bank tellers, and his shimmy down a rope made of sheets, the author is not just entertaining us with page-turning true details of Attila's cops-and-robber misadventures. He is illuminating the stark realities of life in a small country mired in chaos and corruption as it lurches toward democracy. Profoundly human struggles that many of us ignore when they occur in distant lands are brought to life in the pages of The Ballad of the Whiskey Robber. Rubinstein is a multi-talented writer who has a knack for delving into important stories that are missed by others. While this is his first book, he has a history of award-winning stories and articles which have taken him to remote places to investigate unusual subjects and characters. Read his impressive biography here. Here is my recent conversation with Julian Rubinstein: BOOKTHINK: I just listened to the song you've recorded, "The Ballad of the Whiskey Robber." That is beautiful - really, really nice. Have you ever recorded music before?

RUBINSTEIN: I've played music for a long time, but I've never recorded music before. To me it's sort of - well, I like the song, but I consider it a piece of journalism in itself. I'm singing it from his (Attila's) point of view, and of course it's all based on my interviews with him. BOOKTHINK: In the book you mention that when you first heard of the Whiskey Robber, you were sure hordes of journalists would be all over it. They didn't show up. Do you think this was because of the language and distance barrier or because you felt or saw something in this story that they failed to see? What really got to you about this story? RUBINSTEIN: I don't know why other writers missed it because it was so obvious to me it was a great story, as a magazine story, which was what I originally set out to do. I thought for sure that when people heard about this guy who had escaped from prison after committing all these robberies and was a hockey goalie professionally, they would be on it. I was shocked to be the one to not only get there first, but to be the only one to cover it - at least in the States. I don't know why this happened; maybe because it was during the summer, and it was far away. But when I got there and I was able to get a closer look at it, that's when it just stood out - I mean it was working on so many levels, because the characters were so incredible. I couldn't have made them up or thought of better characters - weirder, funnier, crazier, wackier people - and then on top of that it just so clearly told a bigger story of this whole era. Once I saw those things, on top of the great narrative to start with, then I knew it was just about the best story I ever heard in my life. Every corner I turned, there was another unbelievable thing about it. It just kept getting better and better the more I looked at it. BOOKTHINK: It had to take a lot of courage to go do it. You had to know there were going to be a lot of barriers. RUBINSTEIN: Yeah, courage, and maybe stupidity. For one, the financial barrier was probably the biggest one because it cost me a huge amount of money. BOOKTHINK: I was wondering about that. Did you just quit your job and move to Hungary? RUBINSTEIN: I didn't have a job, in that I was a freelance writer. I got a book contract, but let's just say that I definitely went into debt to do it. I had to pay a lot of expenses, the biggest cost being interpreters. I didn't speak any Hungarian, and even by the end I could only say a few phrases. I thought maybe I'd learn, but it's a very difficult language and there was just no way I was going to have any chance of conducting any interviews in that language, unless it was ten years down the road. BOOKTHINK: I can't even pronounce the name of the prison where he's being held. RUBINSTEIN: I can now, but believe me, it took awhile. The pronunciation alone is something to get used to. And then I'd get the pronunciation down, so I'd say a few things there, and people would just assume I could speak the language. They were so surprised because people who weren't native to the area most often couldn't pronounce anything. Then they'd start talking to me, assuming I could speak Hungarian, and of course I couldn't. BOOKTHINK: Aside from the language, what were some of the biggest challenges you faced while working on the story? RUBINSTEIN: Like any story that's involving crime, or really, a lot of stories - there are always people who don't want to talk for some reason - people have their own motivations and they don't always want to help you. I certainly went through a lot of that. I mean, the police weren't very cooperative, not surprisingly, and in addition to that, I was dealing with trying to locate a lot of people who weren't easy to find. A lot of these characters were just scattered around. For instance, the hockey players - it's not like in the States where they are living large, are easy to pin down and have a PR person. I'd run into, "Oh, yeah, he lived here last year and he now he moved there." It was a lot of chasing down leads.

And the language barrier was huge because I went through all the court files, all the police files, thousands of documents, all the newspaper stories, all the TV footage. In the Supreme Court House, for example, I sat there with an interpreter on either side of me, digging through stuff, with each of them calling out bits of information to me and we had to go through more than 10,000 pages of material. Obviously I wasn't interested in 90% of it, but you don't know what you may be interested in until you get through all of it. BOOKTHINK: Did you ever feel like giving up? RUBINSTEIN: Probably. I'm sure I definitely had days. I can't think of one specific example, but I know there were days when it seemed like an impossible mountain to climb. I look back on it now and think how the hell did I do it? BOOKTHINK: What was life in Hungary like when you were there? RUBINSTEIN: It's hard to say because, if you look at it at a glance, you can visit there and think it's OK. The economy is a different thing there; things are a bit cheaper. But not as cheap as my publishers thought it was! Romania, for example, is worse off, and things were much cheaper there. But it's not that cheap to live in Hungary. It's not quite like New York City, but not that much different. My publisher thought the money would carry me a long way over there, but that wasn't the case. People are doing their thing, they're going to work, trying to get by. It's certainly not Third World, but it's not like life in the United States. BOOKTHINK: Is there a middle class similar to that in the U.S.? RUBINSTEIN: Yes, there is, but more like lower middle class. Apartments are really old, really run down. If you've traveled anywhere in Eastern Europe, you've seen that. The people don't drive cars like they do in Western Europe or in America. They drive little cars. BOOKTHINK: Where did you live there? RUBINSTEIN: I lived in the second district, mostly, just across the Margit Bridge in Budapest. I had a little studio apartment - kind of a loft where the bed was sort of hovering above in a very old stone building with cracks, and you definitely felt that sometimes the whole staircase was going to crumble down. Very old Europe in feeling.

|

| Forum | Store | Publications | BookLinks | BookSearch | BookTopics | Archives | Advertise | AboutUs | ContactUs | Search Site | Site Map | Google Site Map

Store - Specials | BookHunt | BookShelf | Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report | DomainsForSale | BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|