|

Storytelling is Alive and Well

|

|

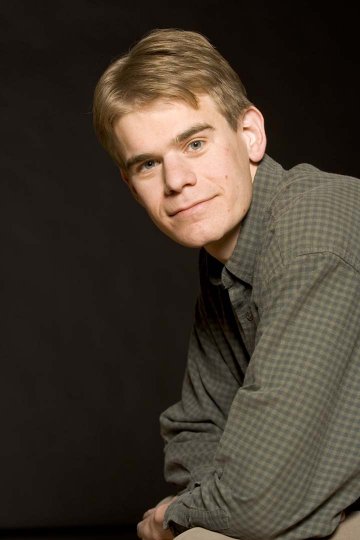

At 33, Nick Arvin is a rising star in the galaxy of American literature. His collection of short

stories In the Electric Eden has received glowing reviews, The New Yorker recently

published his story "Along the Highways," and his debut novel, Articles of War, was

selected as one of Esquire's Books of the Year in 2005.

|

|

|

The American Academy of Arts and Letters has recognized him with the Rosenthal Foundation Award, and he has also been awarded a Michener Fellowship. Nick currently lives in Denver, Colorado, where he is on the faculty of the Lighthouse Writers Workshop.

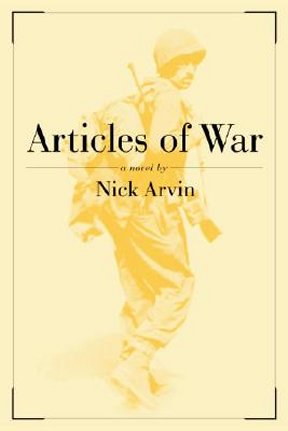

Articles of War is the story of George Tilson (nicknamed 'Heck' for his refusal to use profanity), an innocent eighteen year old from Iowa who is drafted by the Army and sent headlong into combat in World War II's European theater. Though we observe many battles in this book, the most heart wrenching is Heck's battle with his own fear as he struggles to accept his cowardice and the shame that accompanies it. The climax of the book arrives when he receives a dreadful special assignment; this becomes the ultimate collision of his conflicts about himself, his rational fears, and the severe demands of war. Never having been a big fan of war novels, at first I resisted reading Articles of War, but reviews like these convinced me to reconsider: "[A] short, furious novel ... Articles of War presents a tough and visceral vision of war as 'a universe unto itself' and a moral crucible." (New York Times) "Not typical first novel material: a deeply affecting story of a young Midwestern soldier's struggle between courage and cowardice during the last year of World War II, written with such emotional acuity and elegant minimalism that comparisons to Crane, Mailer and Hemingway seem inevitable." (The Journal News) "Shatters the monolithic facade of war ... Articles of War stands out as a surprising achievement for our times ... and far transcends any boundaries of war literature." (The Bloomsbury Review) I am very glad that I overcame my initial trepidation. I enjoyed this novel from first sentence to last, quickly empathizing with Heck. Arvin explores the turmoil and confusion of mortal combat with insightful and graphic detail. Recently, I had the pleasure of talking with Nick Arvin: BOOKTHINK: Thank you for talking with me today. Can you tell us a little bit about your background? ARVIN: I grew up in Michigan. I did my undergraduate work at the University of Michigan, and I completed a master's degree in mechanical engineering at Stanford; from there I went to work for Ford for about three years. I quit Ford when I went to the Iowa Writer's Workshop. BOOKTHINK: You still do some work in engineering, am I correct? ARVIN: I did until about a year ago. I spent about three years here in Denver working for a forensic engineering company. I was basically supporting the engineers to testify as expert witnesses in court cases, primarily working on car crashes and looking at the physical evidence like tire marks and crush to the vehicle, to reconstruct what had actually happened. I was working part-time for them, which was an ideal situation. I quit after the company broke up, but this was right around the time that Articles of War came out. Financially, that book has done pretty well for me, and that gave me some flexibility to take some time off. BOOKTHINK: How long have you been writing? ARVIN: The first fiction that I wrote was in high school. I spent a summer writing several short stories to amuse myself. I probably got the idea from my mother who wrote short stories and some novels. She had one or two stories published in literary journals, but she was never able to sell any of her novels. So I developed a strong sense that writing was a terrible career. Actually, in college, I thought about switching to an English major because I wanted to write. But I ended up sticking with engineering. I enjoyed engineering, and I figured I'd be able to be an engineer and write a lot more easily than I could be a writer and try to work in some engineering in as well. It's nice to have a career that actually pays money to fall back on as a writer. I got serious about writing after I got out of Stanford and while I was working as an automotive engineer for Ford. Ford was a big company, and it was difficult to feel like you were actually getting anything accomplished. That motivated me to focus on the writing. So I would write every evening for a couple hours after I got home from work and kept that up until I got to Iowa. Different things work for different people. But I'm glad I stayed in engineering. I think it gives me a perspective that's a little different from most writers. You don't need to be an English major to write fiction. If anything, it might hinder you because you start thinking in terms of literary criticism. I've never found thinking that way about my writing in advance is helpful at all. I try to think of it as storytelling, and keeping a reader interested. Ultimately you hope to weave in a certain amount of irony and metaphor and things like that, but that's the icing on the cake. BOOKTHINK: You are a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Can you tell us a little bit about it? It's a very old program. Flannery O'Connor was one of their early graduates. It was a wonderful experience for me, I think because I'd had a job as an engineer and had tried to write in the little bit of time I had left over, and when I went off to graduate school to study writing, I had permission to write all day every day. It's a program that really emphasizes getting out of your way and giving you as much time as possible to write. There's one workshop a week where there is a teacher facilitating, and you sit around with maybe a dozen other students and talk about each other's stories. Other than that, the class time demands are minimal. There are other classes you can take, classes offered within the Workshop, literature classes in the English Department - actually you can take classes anywhere in the University. But, you know, I avoided those classes. I mostly wanted to write. BOOKTHINK: How difficult is it to get into the Iowa Writers' Workshop? ARVIN: It's pretty competitive. I think when I was there, about 5% of the applicants got admitted. When you apply, you send in stories and write an essay about why you want to be there and send letters of recommendation - all the things that are usually required in an admissions process. But basically they take out everything except those short stories and give them to a group of students to read. A couple of different students read every story and give them a rating, I think, from 1 to 5 with comments. Those get passed on to the faculty. Frank Conrad was head of the program at that time, and he actually was still going through and reading every application. It was a big thrill for me just to get into the program. BOOKTHINK: You received excellent reviews from a number of distinguished critics for your first novel, Articles of War. Did the book-buying public respond as well as the literary critics? The critics' reviews were really gratifying. In terms of sales, it did quite well, but wasn't a real break-out. One thing that's been interesting to me is people's reaction to Articles of War. Recently, at a book signing in California there was a woman who came up and talked to me about the book. This woman said she didn't usually like war novels, but she really liked this one. That's something several women have said to me ... that they liked this book, even though they don't like war novels. I think that may be because I'm trying very hard in that book to examine Heck's feelings, and particularly fear, which seems like a very rational and obvious thing to feel. But that feeling is often generally glossed over in a lot of writing about war. His emotions make sense for what is going on around him. BOOKTHINK: Your descriptions are vivid. When I read Articles of War, I felt such sympathy for Heck. He was such a likeable character, and it was easy to feel you were there with him. ARVIN: Thank you. I try very hard to find the right words, the right sentence to encapsulate something. I think by natural inclination, if I can say something in a sentence rather than in a paragraph, or in a paragraph rather than a chapter, I'd rather do that. BOOKTHINK: Your writing has been described as "spare, clear, precise" ... do you think you see words and communication differently as an engineer? ARVIN: That's something I wonder about, and I don't know - it's sort of a chicken or the egg thing. I don't know if I became an engineer because I tend to think that way anyway, or to what extent the training in engineering led me to that kind of thinking and writing. But I definitely prize precision and conciseness. There are books that are very wordy and go on and on that are just beautiful, and I love those books too, but I don't try to be that kind of writer.

|

| Forum | Store | Publications | BookLinks | BookSearch | BookTopics | Archives | Advertise | AboutUs | ContactUs | Search Site | Site Map | Google Site Map

Store - Specials | BookHunt | BookShelf | Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report | DomainsForSale | BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC