|

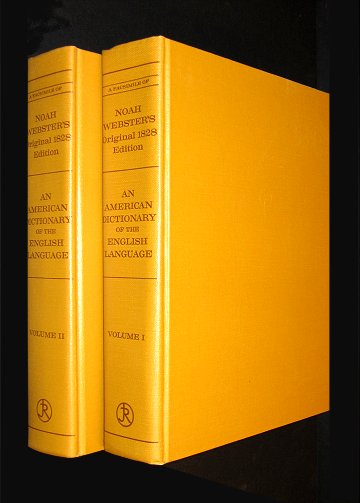

And Why Newer Isn't Always BetterIn a recent BookThinker article, Michael Brook made a telling point about mathematics books: they don't behave like most non-fiction books. Their content doesn't obsolesce as it so often does in other, especially scientific fields. As a result, they often hold their value, sometimes take on more, and it's not unusual for mathematics textbooks to be used in classrooms years after their first appearance. The same can be said of dictionaries but for somewhat different reasons. True, many words more or less retain their meanings over time, but language is a living/dying thing that's forever changing. New words come on board daily; many existing words alter or expand in meaning; slang becomes acceptable usage; some words become obsolete. Yesterday's grammatical taboo often becomes today's shoulder-shrugging why not. Example - a reader recently questioned a BookThinker article's use of the phrase "very unique." Time was that any competent English teacher would have gotten the ruler out and rapped the knuckles of a student who tried to put this one over. H.W. Fowler himself, writing in Modern English Usage (ca. early 1900's), declares with his typically unflinching certitude that "uniqueness is a matter of yes or no only; no unique thing is more or less unique than another unique thing, as it may be rarer or less rare." And later - "it is nonsense to call anything ... very ... unique." In the same breath, however, he cites Charlotte Bronte's use of this very phrase, and Fowler must have known that half the battle was already lost. Today this usage goes almost routinely unchallenged. Merriam Webster's Dictionary of English Usage cites dozens of examples, many taken from highly respected publications, that qualify the word "unique" with abandon - though there's no shortage of conservative grammarians who still follow H.W.'s advice to the letter. Which brings me to dictionaries. Vintage dictionaries are sometimes viewed as noble guardians of language as it should be spoken and written - indeed, how it was before it became "corrupted" by slang, sloppy usage, and so on. I'm old enough to recall the storm of protest that broke out when Merriam Webster published its Third New International Dictionary in 1961. Editor Philip Gove believed that a dictionary's function is to record language as it stands at any moment in time, not to serve as an instrument for dictating how it should be. The result was a production that radically departed from Webster's Second, for decades the standard bearer of correct American English, simply because us chickens weren't speaking/writing that language anymore. This is one important reason why vintage dictionaries retain their value as well as they do, also why Modern English Usage is reprinted ad infinitum. They record what is commonly perceived to be a purer form of English, and having, say, Webster's Second on one's desk - and using it daily - is to some a noble, though perhaps quixotic, defense against creeping permissiveness. But there's another, more subtle reason why "obsolete" dictionaries retain value, and this is often overlooked if not altogether misunderstood. If language becomes corrupted over time, some would point out that this is an indication or marker that society itself has become corrupted. Decadent societies, to continue the argument, are increasingly composed of those who have abandoned the principles that made them great, and, once abandoned, exhibit a weakened capacity to so much as understand these principles, let alone live by them. Language tags merrily along with this, accurately betrays what's happening, and over time - this is where things get sinister - dictionaries like Webster's Third subtly reinforce the march to ruin. Far fetched? Well, consider something as seemingly innocuous as the word "feel." Consult a recent edition of any Merriam Webster dictionary for its meaning, and you'll discover that one synonym for "feel" is "think." Many of us use these two words interchangeably and doubtless feel/think that there's nothing wrong with it. You might be interested to know, however, that in Noah Webster's landmark dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language, first published in 1828, this meaning is nowhere in sight.

No big deal, you say? Hold on. Could it not be argued that the primary reason the two words are now at least partially synonymous is that our society has elevated feeling to the level of thought - that is, feelings are given an importance in today's society that they weren't in Noah Webster's day? And, when you stop to think about it, it's hardly uncommon for feelings to be given even greater importance than thought. "Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law," Aleister Crowley proclaimed, and this ushered in a generation that plunged headlong into indulgent, feel-good living.

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|