|

The Remarkable, Lasting Force of Britannica's 11thIt's no secret that some of the best stuff we come across as booksellers, book collectors or readers isn't always the most timely. Some things last and last, and when we "discover" a vintage title that impacts us in shaking, foundational ways, it's a special joy. Typically, my first thought is, "If this book has been around forever, why the hell didn't anybody ever tell me about it?" The very best fiction can do this. Poetry. Philosophy. However, what isn't widely acknowledged is that sometimes long out-of-print reference works, which we think of as perishable, also rock, and rock on, and on. Take Webster's Second International Dictionary. Long the definitive dictionary of the English Language this side of the pond and a champion of the best that the spoken and written word could be, it was supplanted by a far more permissive Webster's Third in 1961 and, to a great extent, forgotten. (This date also marked the onset, in my opinion, of the erosion of Merriam Webster's standing as a lingual authority.) I was in my thirties before anybody alerted me to this remarkable work, and even then things didn't hit home until I'd found a copy for myself, began using it regularly, and noted some years later that I was deeply indebted to it for the help I received in learning how to think and write with more clarity. While I readily acknowledge that dictionaries appropriately document what language is, not what it should be, and that this is precisely what Webster's Third does, having Webster's Second on my desk to learn what should be is, notwithstanding, crucial to what I do. There are other, similarly superb reference works, some even more unlikely. When was the last time you sat down in your favorite chair and read an encyclopedia? I'm not talking about consulting one - doing research, fact checking, etc. I'm talking about reading one front to back. Never? Well, you're not alone. Most of us haven't. Have no desire to. Encyclopedia articles can be tough going, depending on the topic, and reading even one of them might be more than you'd be willing to take on in a lucid moment. But you might be surprised to learn that a 29-volume encyclopedia published in 1910-1911 was not only uncommonly readable, but also, 104 years later, is still collected for content. In other words, this thing was actually designed to be read, was read, and, most surprising of all, still is read because it's still meaningful. If you've looked at the title of this piece, you already know what I'm talking about - Encyclopædia Britannica's celebrated 11th edition. In print from 1910 to 1928, Britannica's 11th was the standard bearer of human knowledge. It was just what was touted to be in a Cambridge press release: "all that mankind has thought, done or achieved, all of the past experience of humanity that has survived the trial of time and the ordeal of service and is preserved as the useful knowledge of today."

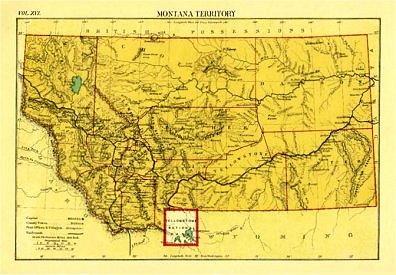

Issued in 29 volumes, the 11th contained almost 29,000 pages of text, 32 full-color maps, over 100 pages of black and white maps, 319 pages of black and white photographic plates, 42 pages of color photographic plates, and thousands of drawings and line art diagrams. Articles varied greatly in length but many numbered 5,000 to 10,000 words and some were literally book length, as much as 40,000 to 50,000 words. It was one of the last essay-format encyclopedias.

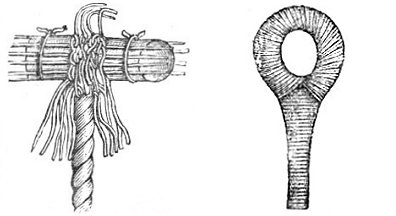

Of course, what made this edition deliciously special were its contributors, over 1,500 of them, and not a lightweight in sight. The 11th was staff-written in part, but many, many notables contributed articles as well. Henry Ford wrote what was to become a classic essay on mass production. Naturalist John Muir, scientist T.H. Huxley and poet Edmund Gosse all penned brilliant pieces. The list of primary sources goes on and on, and even many of the staff-written articles were written by those who later kicked ass - for example, a then unknown Bertrand Russell. But it wasn't just who was doing the writing. It was also how it was written. It was conceived from the outset to be engaging and accessible, something the reading public could actually use. No longer would the encyclopedia be a repository for ponderous treatises. Suddenly, almost as if roused from a deep Victorian sleep, it sprang to life, breathing fresh insight into every imaginable topic. A magnificently complex knot such as the Flemish Eye was dispatched with in simple, workmanlike prose, peppered with striking terminology and pumped into bold relief with blunt, declarative sentence structure: "Flemish Eye (fig. 38). Secure a spar or toggle twice the circumference of the rope intended to be rove through the eye; unlay the rope which is to form the eye about three times its circumference, at which part place a strong whipping. Point the rope vertically under the eye, and bind it taut up by the core if it is four-stranded rope, otherwise by a few yarns. While doing so arrange six or twelve pieces of spun-yarn at equal distances on the wood and exactly halve the number of yarns that have been unlaid. If it is a small rope, select two or three yarns from each side near the centre; cross them over the top at a, and half-knot them tightly. So continue till all are expended and drawn down tightly on the opposite side to that from which they came, being thoroughly intermixed. Tie the pieces of spun-yarn which were placed under the eye tightly round various parts, to keep the eye in shape when taken off the spar, till they are replaced by turns of marline hove on as taut as possible, the hitches forming a central line outside the eye. Heave on a good seizing of spun-yarn close below the spar, and another between six and twelve inches below the first; it may then be parcelled and served; the eye is served over twice, and well tarred each time. As large ropes are composed of so many yarns, a greater number must be knotted over the toggle each time; a 4-in. rope has 132 yarns, which would require 22 knottings of six each time; a l0-in. rope has 834 yarns, therefore, if ten are taken from each side every time, about twice that number of hitches will be required; sometimes only half the yarns are hitched, the others being merely passed over. The chief use of these eyes has been to form the collars of stays, the whole stay in each case having to be rove through it a very inconvenient device. It is almost superseded for that purpose by a leg spliced in the stay and lashing eyes abaft the mast, for which it is commonly used at present. This eye is not always called by the same name, but the weight of evidence is in favor of calling it a Flemish eye." Do you get the sensation of verbs actually having muscle here?

If a trip to our beloved Baghdad was contemplated, why, it could be accomplished imaginatively in the pages of the 11th: "The town has been built without the slightest regard to regularity; the streets are even more intricate and winding than those in most other Eastern towns, and with the exception of the bazaars and some open squares, the interior is little else than a labyrinth of alleys and passages. The streets are unpaved and in many places so narrow that two horsemen can scarcely pass each other; as it is seldom that the houses have windows facing the thoroughfares, and the doors are small and mean, they present on both sides the gloomy appearance of dead walls. All the buildings, both public and private, are constructed of furnace burnt bricks of a yellowish-red color, principally derived from the ruins of other places, chiefly Madain (Ctesiphon), Wasit and Babylon, which have been plundered at various times to furnish materials for the construction of Baghdad." Built on the bones of the dead, it was. And adaptations to a climate that was brutally hot by day and yet surprisingly, bracingly cool by night were expressed in architecture inhabited by the elite class: "The houses of the richer classes are regularly built about an interior court. The ground floor, except for the serdab, is given up to kitchens, store-rooms, servants quarters, stables, etc. The principal rooms are on the first floor and open directly from a covered veranda, which is reached by an open staircase from the court. These constitute the winter residence of the family, reception rooms, etc. The roofs of the houses are all flat, surrounded by parapets of sufficient height to protect them from the observation of the dwellers opposite, and separate them from their neighbors. In the summer the population sleeps and dines upon the roofs, which thus constitute to all intents a third storey. The remainder of the day, so far as family life is concerned, is spent in the serdab, a cellar sunk somewhat below the level of the courtyard, damp from frequent wettings, with its half windows covered with hurdles thatched with camel thorn and kept dripping with water. Occasionally the serdabs are provided with punkahs." Don't know what a punkah is? Well, the 11th has a dedicated entry for it: "strictly a fan," it asserts. "In its original sense the punkah is a portable fan, made from the leaf of the palmyra; but the word has come to be used in a special sense by Anglo-Indians for a large swinging fan, fixed to the ceiling, and pulled by a coolie during the hot weather." Hmm. Couldn't we all use our own coolies. Closer to home, the 11th also offered some insight into book collecting: "On the other hand so long as a book (or anything else) is and appears likely to continue to be easily procurable at any moment, no one has any reason for collecting it. The anticipation that it will always be easily procurable is often unfounded; but so long as the anticipation exists it restrains collecting, with the result that Horn-books are much rarer than First Folio Shakespeares. It has even been laid down that the ultimate rarity of books varies in the inverse ratio of the number of copies originally printed, and though the generalization is a little sweeping, it is not far from the truth." In his autobiography, Another Part of the Wood, Art historian Sir Kenneth Clark writes: "One leaps from one subject to another, fascinated as much by the play of mind and the idiosyncrasies of their authors as by the facts and dates. It must be the last encyclopedia in the tradition of Diderot, which assumes that information can be made memorable only when it is slightly coloured by prejudice. When T.S. Eliot wrote "Soul curled up on the window seat reading the Encyclopædia Britannica he was certainly thinking of the eleventh edition." If you haven't encountered the 11th in your own reading, are you intrigued? Many readers are, and the encyclopedia still commands top dollar, even in the 12th and 13th editions, which, in addition to supplementary volumes, contain the original 29 volumes of the 11th. If you're interested in sampling more of the 11th but not ready to cough up a few hundred dollars, it's now in the public domain and presently (but only partially) available at http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/. I offer this link grudgingly. Note that these excerpts appear to be raw scanned text and contain many typos - and in fact spoil the experience almost entirely for me. A complete, edited CD version (somewhat pricey) is also available at http://classiceb.com/order.html. If you're patient, an online edition is being assembled at Project Gutenberg, but be prepared for a lengthy wait. As of this date, only part of the letter "A" has become available. Yawn. 44 million words does take time. Finally, here's an excellent and widely available anthology of some of the best and brightest articles, and this is my recommendation for a good place to start: All There is to Know (1994), edited by Alexander Coleman and Charles Simmons. Subtitle: "Readings from the Illustrious Eleventh Edition of the Encycloædia Britannica." ISBN 0-671-76747-X. This may be purchased on BookThink's BookShelf page. Given the desirability of the 11th edition, there is obvious potential here for booksellers, and I'll get into more detail about this and, while I'm at it, encyclopedias in general in today's Premium Content. If you aren't yet a subscriber to the BookThinker email newsletter, note that Premium Content is available only by subscription and does not - and may never - appear on the website. Subscriptions are free and may be initiated on most BookThink web pages. NOTE: Gold Edition replaced regular Premium Content on August 2, 2004. Learn how to subscribe.

< to previous article

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|