|

Papyrus

|

|

At first glance, a discussion of papyrus might not seem pertinent to BookThink readers,

but there are more connections here than you might think. A bibliophile myself, I always thought

the word root biblio meant book. Well, not exactly. Byblos is actually the

Greek word for papyrus, so called because Byblus, a Phoenician city, was the ancient center

for papyrus exportation.

Papyrus was used for writing, so the Greek word for book is biblion and was since adopted by

Latin speakers, spawning words in the Romance languages for library and the English word

bibliography.

|

|

Our word paper also comes from papyrus, first from Greek, then through Latin and French, and finally adopted by Middle English. (By the way, some forty percent of English words today come from the French language, thanks to William the Conqueror.) It's also interesting to note that the English/Germanic word book derives from the Germanic word for beech tree. Romans used peeled beech bark in much the same way that Egyptians used papyrus.

Books as we now know them evolved from scrolls, and many of the earliest scrolls were made from papyrus. Today's readers may have trouble relating to the use of scrolls - that is, outside of Jewish temples and anachronous royal agencies in Britain - but the Bible itself was first copied onto papyrus and only later circulated in actual book form (codex). Although not shaped the same way and a little more cumbersome, scrolls served the same function as a handheld paperback does today.

Human use of the papyrus plant is an excellent example of the ageless need to communicate: to record one's thoughts, to document official business, and to send letters to friends or a loved one. To most of us living in the twenty-first century, papyrus is symbolic of ancient life.

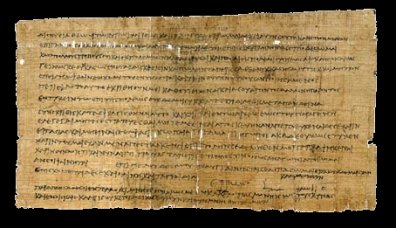

Ancient papyrus was a species of reed that grew on the banks of the Nile River in Egypt. The portion of the plant used for writing came from the pith in the stem of the plant and was pounded flat and thin. Oddly enough, no glue was needed to attach the segments which comprised the scroll. The natural gum of the plant, moistened with Nile water, was sufficient to bind the sheets together.

An early precursor to paper, papyrus was thin, pliable, and lightweight. It was sold in rolls and could be cut into smaller pieces for letters, documents, books, and literary creations. In Egypt and throughout the Mediterranean, papyrus was used until the eighth century. It was often recycled, used on both sides, and reused for mummy wraps!

The efficient production of durable books may be something we take for granted today; by contrast, papyrus scrolls were both laborious to produce and notoriously fragile. Pieces would often rip, break off, and at times altogether disintegrate. Inevitably, today's scholars are left with only bits and fragments of a huge, mysterious puzzle.

The Duke University Papyrus Archive informs us that, "Only the climate of Egypt and certain parts of Mesopotamia favor the preservation of papyri in the debris of ancient towns and cemeteries." Of course, Egypt's dry climate not only retarded the biodegradation of papyrus but that of mummies as well. Not so in Rome and Gaul, where texts were exposed to more moisture and required constant recopying. Papyrus weakened with even just one fold, so it was useful only for rolling into scrolls. Parchment was much more durable and soon rendered this fragile reed obsolete.

Ancient papyrus is brittle, not unlike baked filo dough in a Greek pastry, and appears so fragile that it seems even a small puff of air would blow it to shreds like a dandelion gone to seed. Not surprisingly, there isn't much left for collectors. Today, around 400,000 ancient papyrus texts and documents are preserved around the world, about 50,000 of them published after 1788. These collections, as you might suspect, are largely fragmentary, surviving only as pieces of much larger documents. Quality of ancient papyrus varies with conditions present at the burial site - most importantly, moisture content and the presence of insects.

Museums conserve fragments and place them under glass to retard further deterioration. Since many of these arrive from archaeological digs with significant damage, they often require both cleaning, flattening and reassembly before being put on display. Acid-free paper tape is used to join fragments, and restored specimens are usually framed behind glass or mounted on board or paper with pressure-sensitive tape, then stored in flat acid-free boxes in climate-controlled areas.

In June 2003, Sotheby's auctioned 29 papyri fragments on eBay. These were discovered in Egypt in 1897 and dated between the first and fifth centuries. Oxford scholars sponsored by the Egyptian Exploration Fund donated the fragments to the Colgate Rochester Divinity School after the turn of the century. Understandably, some scholars were in uproar, concerned that the items would end up in private collections, but in the end, the mighty dollar spoke louder than the principle of public access, and $646,000 was taken in.

Despite this figure, papyrus fragments are sometimes very affordable. In 2003, Aspire Auctions sold several, each approximately 3 inches square and displaying a few words of Coptic or Greek text, for between $25 and $120! Not bad for artifacts dating back to the seventh and eighth centuries. In 2004, the same company auctioned two smaller scraps, one bearing the word s" law, the other neither, and each brought $92. Similarly, a recent eBay auction for a 2-inch-plus fragment closed at just over $60, though another, somewhat larger piece, sold for well over $600. In general, the larger the scrap or amount of writing, the higher the price. Greek and Coptic papyri for sale at Sotheby's this year hovered in the $1,000 to $2,000 range for larger fragments.

It's a sad truth that, as prices go up on printed matter, forgeries tend to proliferate, and papyrus is no exception. Sometimes careful scanning with an electron microscope is necessary to verify that pigments are authentic.

Today, papyrus continues to be produced on farms, and some is marketed as being chemically and physically identical to ancient papyrus. Among other things, sheets are used by artists and crafters, often for painting/expressing Egyptian themes or achieving a look of antiquity.

The ancient Egyptians probably weren't fully aware how short-lived their documents would be, how much of their remarkable history would be lost forever, but although we've greatly improved the longevity of printed matter in the intervening centuries, in some ways we're no less vulnerable to the same fate. A world war or natural catastrophe could easily shut down the global Internet, and imagine how much would be lost. Someday I may add a papyrus fragment to my book collection as a reminder of that first great age of learning and communication.

And a reminder to back up my hard drive!

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

Contact the editor, Craig Stark

editor@bookthink.com